Jiggers: a painful infestation

Jiggers: a painful infestation

Many people living in tropical or sub-tropical regions are exposed to the risk of a debilitating infestation of these tiny sand-fleas, yet little is known of their epidemiology. New study from Kenya shows how common they can be.

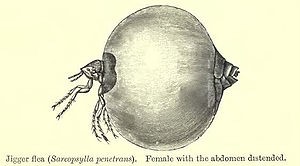

A jigger infestation, known as tungiasis, can be very painful; I speak from personal experience. This tiny sand-flea has a variety of other colloquial names including nigua, chigoe and bicho de pé (Portugues for foot-bug). The last one, and its scientific name, Tunga penetrans, giving clues to its habit, as the adult female burrows into the skin, usually of the foot.

Originally endemic in pre-Columbian Andean society and the West Indies jiggers were spread to other tropical and sub-tropical regions via shipping routes. They are now present in the Caribbean, Central and South America, sub-Saharan Africa, and India, but not in Europe or North America.

The jigger life cycle

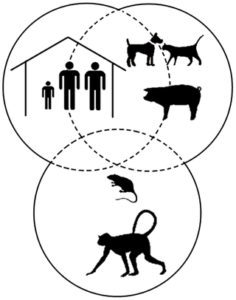

Jigger larvae live a few centimetres under sand or soil, feeding on organic matter. They are often found inside dwellings with mud floors. The larvae moult to adults about 1mm in size and move to the skin of a variety of mammals including rats, domestic animals and humans.

Unlike males, the females burrow into the skin leaving just the tip of their abdomen exposed, thus enabling them to exchange gasses, defecate and mate. The females feed on blood by inserting their proboscis into dermal capillaries. They quickly swell as they become full of eggs which are shed into the environment, after which the females die.

Pathology

Penetration of the skin causes intense itching and is followed by inflammation and acute pain. The jigger is evident as a small swollen lesion, with a black dot at the centre, which can grow to the size of a pea.

Severe pathology following an infestation is caused by bacteria entering the skin when the jigger penetrates. These infections can lead to abscess formation, tissue necrosis and gangrene. Tungiasis has also been associated with tetanus, possible due to the entry of the soil pathogen, Clostridium tetani into the wound. In addition, Wolbachia bacteria, present in the jigger, release inflammation-inducing lipopolysaccharides into the surrounding tissue when the females die.

The risk of acute pathology can be prevented by removal of the jigger with a sterile needle and disinfection of the affected area. However, in poor rural or shanty-town settings non-sterile objects are often used to winkle the jigger out, including thorns or non-sterile pins, thereby introducing more bacteria.

Epidemiology

Jiggers are endemic in many tropical and sub-tropical countries, but the epidemiology of the disease is poorly understood. In common with most neglected tropical diseases, the children and the elderly are the most likely to be affected by tungiasis. A recent study by Ruth Monyenye Nyangacha and colleagues aimed to asses risk factors and the health burden associated with this disease.

Tungiasis in Kenya

The study was based in 21 villages in Vihiga County, Kenya, and assessed 437 participants aged over 5 years for the presence of a jigger infestation. Socio-economic factors were assessed via a questionnaire. The area is densely populated and almost 80% of people live in houses with earthen floors. The soil in all study village was a sandy clay.

Just over 20% of participants were found to be infested. Five of the villages had no cases of tungiasis and three represented hot spots for infestation. Village altitude did not affect distribution of infestations in the study area, however factors associated with low economic status factors were significant, including:

- Going barefoot or wearing open toed footwear

- Illiteracy

- Lack of toilet facilities or electricity

- Washing without soap

- Houses with earthen floors

- Having a common resting place in the house

- Having rats around the house

Importantly, 45% of the participants in the study did not know how tungiasis is transmitted. It was associated with witchcraft, being cursed or, in the elderly, impending death.

The study also showed that 5-14-year-olds were particularly vulnerable, probably as they play barefooted around their houses and are also exposed to infestation when attending schools with earthen floors.

The authors recognise the modest scale of their study and point out several factors that could be important in future studies such as the inclusion of under-fives, topography and soil type studies and the conduction of longitudinal studies that may identify cause and effect, looking at one variable at a time.

These findings reinforce previous studies performed in other areas and point to the likelihood of transmission occurring where people gather to rest or sit for long periods, as jigger eggs could be shed there, and the whole lifecycle take place in that location. In particular, the finger points to poor rural schools which do not usually have concrete floors in the classrooms.

The report highlights preventative measures such as the need for education regarding transmission and hygiene, the importance of wearing protective footwear and the possibility of spraying the floor of areas were transmission could occur with insecticides.

The World Health Organisation does not officially recognise tungiasis as a neglected tropical disease and no systematic data on disease occurrence is available. Perhaps it is time this is remedied. Meanwhile avoid wearing open toed footwear if visiting areas where transmission could be occurring.

Watch Full Video 👇